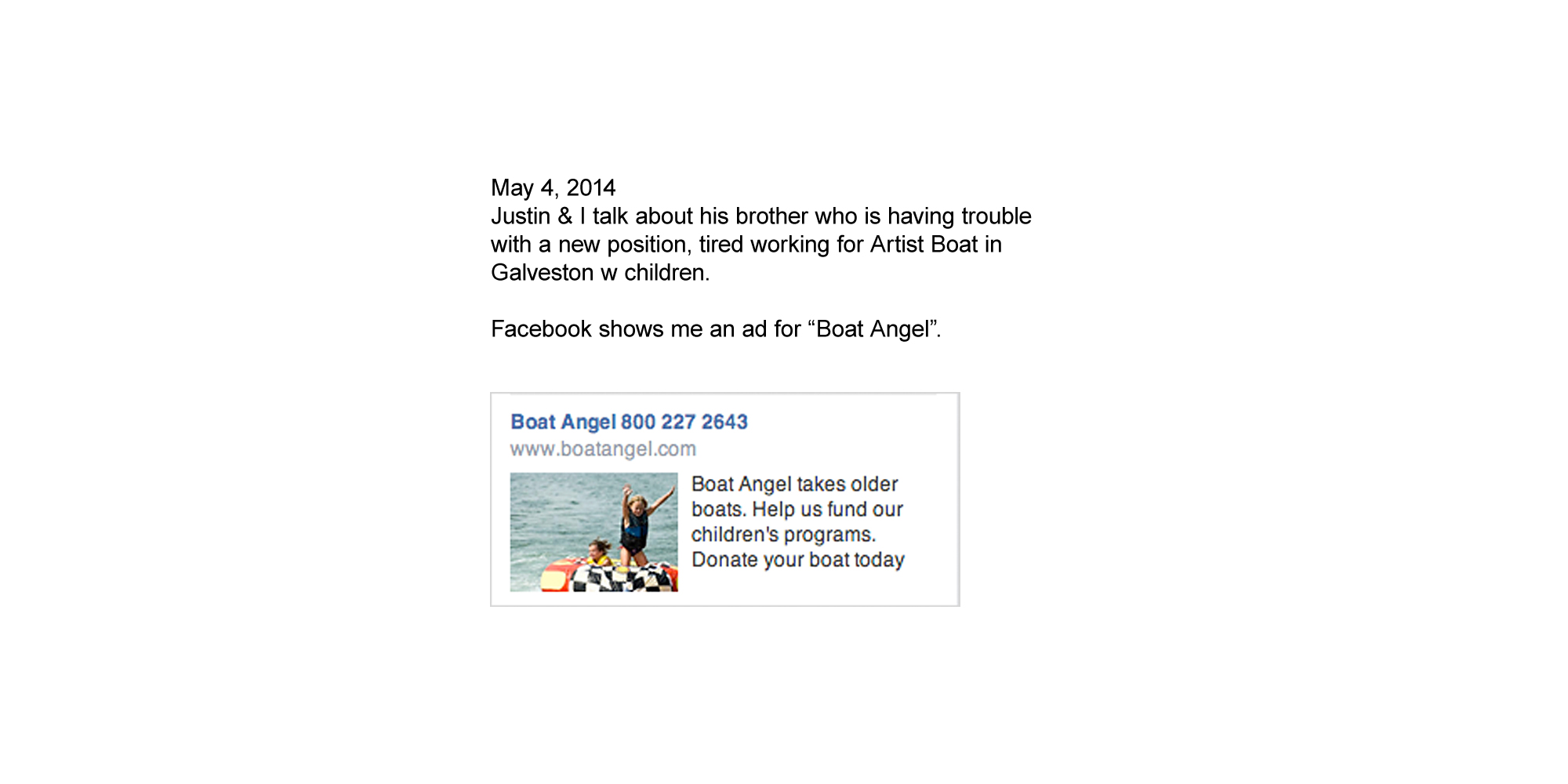

Log, phone conversations and Facebook ads, 2013-2014

I suspect that topics and subjects that I talk about while on my smartphone, or when my smartphone is on and nearby during a conversation, are later shown to me in ads on Facebook online. In each instance presented in this log, I do not recall searching the topic on the internet, text, or entering the keyword in any way on my phone or on a computer.

Are these instances coincidences, or hard evidence that my conversations are being mined by marketers? Innate cognitive biases can trick humans into perceiving patterns that aren’t there. What is certain is that after Snowden’s revelations, I am convinced that it is likely corporate collection and processing of my verbal communications is happening without my knowledge.

It is possible for a company to record audio anytime through an app on my smartphone, send and process audio using data recognition through built in software on my device, and build a user profile using my unique phone ID number. While I would need to work with a technology expert to fully research and prove my theory, keywords collected from my audio data paired with my unique phone ID could be used to personally customize ads with a Facebook marketing partner.

My phone runs on an Android system, and comes with voice recognition software that cannot easily be disabled. Wired wrote in 2013 that

When you talk to Android’s voice recognition software, the spectrogram of what you’ve said is chopped up and sent to eight different computers housed in Google’s vast worldwide army of servers. It’s then processed, using the neural network models built by Vanhoucke and his team. Google happens to be very good at breaking up big computing jobs like this and processing them very quickly. 1

Certain apps can turn your phone microphone on even when you are not making a call, as noted in the article “I Know My Phone’s “Spying” on Me, But How Bad Is It?” online in Lifehacker in 2011.

Sometimes what seems completely unnecessary (and kind of scary) can still have an actual function. Shopping rewards app ShopKick, for example, appears to turn on your microphone and record audio without you knowing about it. If you installed this shopping rewards app, you probably didn’t notice or think much about the permissions setting that allowed ShopKick to record audio and take pictures. ShopKick’s privacy policy suggests the company is using that recorded information to tell if you’re listening to a commercial or show on TV, maybe to tell more about you so it can tailor the discounts or ads it sends you. Yes, that’s creepy. But ShopKick’s audio listening may also serve a necessary purpose: to listen for a tone within a store (inaudible to us) so it can tell if you’re in a participating store, according to the New York Times. 2

After reading this I took a quick look through the app permissions on my phone. It turns out that I use a Google product constantly, the Maps application (version 6.14.5), that requires in its permissions that the application have access to phone hardware controls, to record audio. I am surprised.

In April 2014, KUTV in Utah

asked Google why they need to access a microphone for a mapping program. They said it allows users to use a speech function within the app that allows a user to speak the destination and then the app will route a course. 3

This explains why Google needs to access the microphone for the functionality of its app, but the statement does not exclude other possible uses of my speech data that Google may collect without my consent. In the last year, I talked about my phone listening to me with a tech person on an airplane headed for SXSW in Austin, a programmer friend who is in the midst of a new startup, and both dismissed my concerns. It seems that no one is taking this potential breach of privacy seriously. In 2011, Dan Rua, Managing Partner of Inflexion Partners, an early-stage venture capital fund wrote on his Florida Venture Blog that

Given all the coverage of iPhone, Android, Blackberry and Windows Mobile apps lately, I’m surprised I’ve seen relatively little discussion of the new privacy issues some apps present, particularly when they leverage phone resources such as the microphone. Microphone spying may have been a small issue when many desktops didn’t have microphones or microphones were stuck wherever the computer sat, but the ubiquity and proximity of smartphone microphones opens a new roving bug risk that extends beyond the phone owner to anyone nearby. 4

Perhaps these privacy issues are simply accepted by most people as the cost of access to technology through commerce in the twenty-first century. Tech companies provide services in exchange for your personal information. Scott Thurm and Yukari Iwatani Kane of The Wall Street Journal wrote in 2010 that

Few devices know more personal details about people than the smartphones in their pockets: phone numbers, current location, often the owner’s real names, even a unique ID number that can never be changed or turned off…smartphone apps collect and broadcast data about your habits. Many don’t have privacy policies and there isn’t much you can do about it. These phones don’t keep secrets. They are sharing this personal data widely and regularly, a Wall Street Journal investigation has found. An examination of 101 popular smartphone “apps games and other software applications for iPhone and Android phones showed that 56 transmitted the phone’s unique device ID to other companies without users’ awareness or consent. Forty-seven apps transmitted the phone’s location in some way. Five sent age, gender and other personal details to outsiders. The findings reveal the intrusive effort by online-tracking companies to gather personal data about people in order to flesh out detailed dossiers on them. 5

Facebook officially does not specifically discuss where its marketing partners get data, except to say that “Advertisers and their marketing partners can also reach you using information they already have. in a section on their website “Advertising on Facebook”. 6

-June 2014

1 Robert McMillan, “How Google Retooled Android With Help From Your Brain”,” Wired, http://www.wired.com/2013/02/android-neural-network/, (February 18, 2013).

2 Melanie Pinola, “I Know My Phone’s “Spying” on Me, But How Bad Is It?,” http://lifehacker.com/5864518/is-my-phone-spying-on-me-and-what-can-i-do-about-it/all, (December 2, 2011).

3 KUTV, “Good Question: Is My Cell Phone Spying On Me?,”http://www.kutv.com/news/features/gephardt/stories/good-question-my-cell-phone-spying-me-302.shtml, (April 23, 2014).

4 Dan Rua, “FlexiSpy, ShopKick, Roving Bugs and a New Breed of Spyware?,” ÂÂÂhttp://floridaventureblog.com/2011/01/shopkick-flexispy-roving-bug-spyware.html, (January 5, 2011).

5 Scott Thurm and Yukari Iwatani Kane, “Your Apps Are Watching You A WSJ Investigation finds that iPhone and Android apps are breaching the privacy of smartphone users”, http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052748704694004576020083703574602, (December 17, 2010.

6 https://www.facebook.com/about/ads/#relevance, (retrieved May 31, 2014).